BIOGRAPHY

This biography was made possible by the diligent research of Myron Buck and the kind contributions of the members of the TalkBass forum, who have kept John Klingberg's memory alive in a discussion thread started in 2007.

Early Life

John Robert Klingberg (November 17, 1945 - January 22, 1985) was an American bassist noted for his innovative contributions to two Van Morrison albums, Moondance [1] and His Band and the Street Choir [2]. His work is characterized by a unique style of walking bass, as heard on songs such as "Into the Mystic" and "Moondance." His bass can be heard on some of Van Morrison's highest-charting singles, including "Domino," "Blue Money," "Come Running," and "Call Me Up In Dreamland."

Born in Chicago, Illinois to parents Arthur and Margaret Klingberg, his large family was of German and English ancestry. He was the youngest of seven children, with all his siblings between 11 and 25 years older than him, making him effectively a different generation than his brothers and sisters. The family lived in McHenry, Illinois, in a small house in the Mineral Springs neighborhood. A lifelong music lover, in 1963 Klingberg convinced his father to send him to Berklee College of Music in Boston, which took considerable persuading, according to his Berklee classmate.

The Boston Years

In 1960s Boston, folk, jazz, R&B, early rock'n'roll, and youth culture were taking root, and Klingberg quickly became involved in Boston's burgeoning music scene, eventually dropping out of Berklee. He was heavily influenced by classic R&B and jazz, especially James Brown, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, and Miles Davis, as well as by rock bands of the era such as Cream and The Jimi Hendrix Experience.

Klingberg remained in Boston after he left Berklee. From 1963-65, Klingberg was playing trumpet in a band called Randy And The Soul Survivors (along with singer Randy Madison, saxophonist Jack Schroer, Steve Hall on guitar, Al Leto on bass, and John Hall on drums) [3].

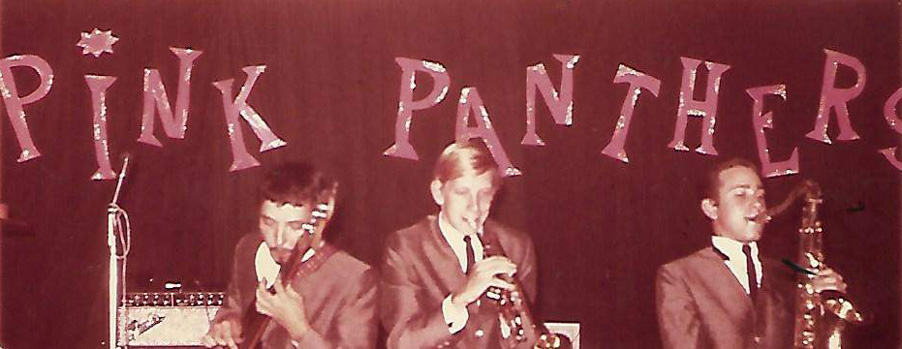

The Pink Panthers in 1966 at the Crown and Anchor in Provincetown, from left, Paul [last name unknown], John Klingberg, and Mitch Schere

Sometime in 1965, Klingberg switched to bass, though he continued to play trumpet, playing both instruments in the The Pink Panthers [4] (with Roger Baker on piano, 'Bat' Kaddy on drums, Paul [last name unknown] on bass, and Mitch Schere and Jack Schroer on sax), Third World Raspberry (with Don Renfro on drums, Herbie Edwards on vocals, and Bruce 'SJ' Bernstein on guitar) [6], and Dario and the Rainbows (with John Muse on saxophone [7] and Rich Mayer on drums [5] [8]). This switch to bass was likely motivated by the burgeoning rock'n'roll scene, but also by his collapsed lung, a condition that made him ineligible for military service. His Boston girlfriend (whom he married in 1969) recalls the struggling musicians earning a living in the nightclubs:

The nightclubs had a very 50's kind of crowd, really square, like a cheesy Las Vegas club. I don't remember much about the other bands the guys played in, except that one had girl twins as backup singers and the other was fronted by a sweet giant of a black man named Julius. By that time, John had long hair and he tied it in a ponytail and stuck it under his suit collar. I think Jack [Schroer], Mike [Winfield], and Collin [Tilton] did, too. They had to wear suits and ties and do 'steps'... it was very funny to see. John and I went to a musician's clothing store in downtown Boston, where he bought French cuff shirts and giant blue rhinestone cufflinks. They all wore those shirts and cufflinks on stage. When they played, the suit sleeves pulled up and the stage lights hit the cufflinks and the rhinestones shot sparks into the audience. John's shirts were very plain, but Jack had shirts with ruffles. He could pull it off though and he looked great. [12]

Lynn Prior, drummer for Randy and the Soul Survivors and a Berklee classmate, recalls the switch to bass:

I went to Berklee at the same time as John and was Jack Schroer's roommate for the first year. John quickly became one of our group, both socially and musically - he was one of the funniest people I have ever met. He could talk for half an hour about how his family tried different schemes to dissuade him from a music career and we would be gasping for breath the entire time.

There was a very active music scene in Boston at that time and we had many weekend gigs. When we came back for second year, Randy Madison hired Jack, John and guitarist Steve Hall for his group. He already had a drummer so I was left out. After New Year's Eve in 1965, the drummer had a personal problem and I replaced him. Randy and the Soul Survivors rose rapidly on the local scene. We were playing weekends at a bar near the docks, which featured dancing hookers for all the seamen. We went from that to playing at the colleges with past rock stars. They would do their show and afterwards we would play for dancing. When the school year ended so did those gigs.

I remember one afternoon we were talking about how we might be able get more gigs as a rock band and John said "I can play bass." At the time I don't think anyone took him seriously as he had never mentioned it before in two years. [12]

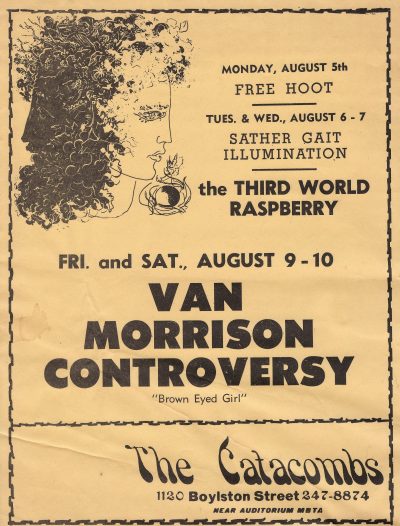

Klingberg dropped out of Berklee after two years, but continued to play bass in these bands as part of the 'Bosstown Sound' of the 1960s, living on Tremont Street with the members of Third World Raspberry, later moving to Columbus Avenue [10]. Third World Raspberry achieved a modicum of success in the Boston scene, playing in small clubs such as the Psychedelic Supermarket, the Unicorn, and the Catacombs, where they shared a bill with Van Morrison - billed as "Van Morrison Controversy" - in August 1968, though this was before he was introduced to Klingberg. The original band's founder, Ted Scourtis, left before Klingberg joined. He recalls:

John Klingberg and [Renfro] were THE professional musicians of the group, with great resumes and chops. Donny was, at the time, one of the few white drummers that had mastered "Fat Back" drumming, and I believe had played with some of the top R&B cats of the day. John's story was similar, and of course, he went on to play with Van Morrison on Moondance and Street Choir. [9]

We recorded in Columbia Studios in New York City. The vice president was there and was talking about hit songs and whatnot. We couldn't finish all the songs because [vocalists] SJ and Herbie couldn't sing because they kept laughing. They had smoked something on a break and couldn't stop laughing during the singing recording. We came back to Boston to return and finish everything at another date.... One night we were supposed to play at the Catacombs and me and John were sitting around at home smoking waiting for someone to come and get us. Suddenly in walked Herbie with a beautiful blond and announced that he was going to California. He left and we never saw him again. That was what happened to The Third World Raspberry. [9]

Saxophonist Collin Tilton recalls the circumstances that led to the formation of the Moondance band:

Morrison was not happy with the rhythm section from Colwell-Winfield Blues Band, so asked them if they knew anyone else. Jack Schroer brought Van Morrison over to meet Klingberg. According to his former wife:We were all living in Woodstock and playing in a group called the Colwell-Winfield Blues Band. We were working on our second record and our leader fired the singer without having a replacement lined up. At about the same time, Van fired his band. He was doing what was going to end up being the Moondance album. They were rehearsing or something and he fired everyone in his group. One thing led to another, and we all ended up jumping ship. Jeff Labes [pianist] was a member of Colwell-Winfield. Jack Schroer and myself were also in the band. John Klingberg, who played bass on Moondance, was a friend but wasn’t a member of the Colwell-Winfield group. The drummer, Chuck Puro, cut a couple of songs and then got out of there; he wasn’t happy. I had never heard of Van Morrison at the time. Everyone else was going to play with him, though, so I went along. [11]

John was not doing studio work when I was with him. Before Van, he and Jack and Collin took any work they could get, which included playing the "standards" out of fake books in nightclubs. John and Jack were friends from Chicago. They had driven back and forth many times and talked about road trips in Jack's car, which he called a 'short.' Jack was a hipster and he talked like that.

Van and Jack rang the brownstone bell, John and I went down, Van and Jack were standing on the street, we all said hello, the men left together. They went somewhere to play (maybe the Unicorn?), it was during the day, I did not go with them. Later, when John came back, he said he got the gig. He did not have to "work his way in," Van heard him play and that was that. John had a slightly dragged out, slightly behind the beat way of playing that Van was looking for. [12]

Morrison had left the Northern Irish rock band Them in 1966 and moved to Boston, then achieved critical, but not commercial, success with his 1968 solo album Astral Weeks. Rejecting the musicians his record label provided, he put together an ensemble-style band of horns, strings, drums, keyboard, and backing vocalists, hiring Klingberg on bass, and from Colwell-Winfield, Jeff Labes on piano, and both Tilton and Schroer on saxophone. [12]

Woodstock and Van Morrison

Later in 1969, Morrison moved to Woodstock, New York and began writing songs for his next album. Schroer was already living in Woodstock, and Klingberg and the rest of the band moved there as well. However, Moondance was recorded in New York City's A&R Studios in August and September 1969, not in Woodstock. According to his former wife:

Moondance was released in January 1970, and quickly became a critical and commercial success. In subsequent years, it was awarded gold, platinum, and multi-platinum sales awards by the RIAA, having sold over 3 million copies.Van hired five limousines to transport the band, but it was exhausting to travel to New York City and back to record for months, it was two hours each way. (That's what the Street Choir song "I've Been Working" is about: "Been up the thruway, down the thruway, Up the thruway, down the thruway, Up, down, back and up again.") It was making everyone nuts (I was at some of the Moondance sessions, with other wives and babies, but it was too much for us), so Van tried to record in Woodstock (some huge theater?) but he could not get the sound he wanted. Then David Shaw (who later changed his name [to Dahaud Shaar]) set up a shack to record it. Van tried it and that only lasted a few hours. [13]

Klingberg on stage with Van Morrison and the band at the Fillmore East in 1970

His former wife recalls the touring years:

Van Morrison went from playing in small Boston clubs to performing in large venues, symphony halls, and even stadiums, sharing the bill with top bands such as The Byrds, Jethro Tull, The Moody Blues, John Lee Hooker, and the Allman Brothers. The Moondance band accompanied him, touring throughout the United States, playing in both the Fillmore East and West, with performances in every month of 1970. [14]They toured a lot after Moondance was released and was a huge hit, which surprised all of them, even Van. They seemed to always be on the road, but were making a lot of money and for people so young, that was great. At first, the wives and babies came along, but touring is exhausting so we gave up and stayed home and spent our time with each other. It seemed like they toured constantly until the recorded the next album (Street Choir).

They stayed in upscale hotels, mostly, and I was with John and the band. We were young and very impressed with how fancy it was. Van would rent large suites for the band and since everyone was in their early 20s, that was a lot of fun. [13]

Moondance was followed by His Band and the Street Choir in November 1970, which was also well-received by critics and fans. Originally titled Virgo Clowns, Warner Bros renamed the album without Morrison's consent. For this album, Morrison carried over only three musicians from the Moondance sessions: Schroer, John Platania (guitar) and Klingberg. Klingberg joined Morrison on tour, however Morrison was known to be 'testy' and difficult to work with, which caused several members of his band to continue to seek other opportunities to play and record. [10]

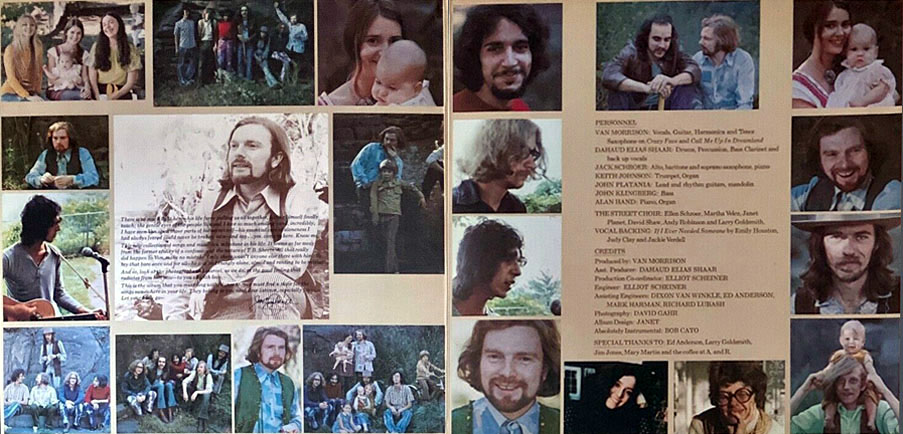

Van Morrison's band was photographed in his garden in Woodstock by Elliot Landy in 1969 for the sleeve of His Band and the Street Choir.

Morrison asked several of his musicians to relocate to California, where he had moved with wife Janet in early 1971. According to Klingberg's former wife, Morrison paid for him and his family to relocate, but once they arrived, he did not start studio work for months afterward, forcing most of the band to find other jobs. [13] Morrison's own account differs. In 1990, he told London disc jockey David Jensen that pressure from his label caused the replacement of his band:

When Morrison started working on his next album, Tupelo Honey, in spring of 1971, Klingberg was not part of the band. Of the Moondance musicians, only saxophonist Jack Schroer contributed to Tupelo Honey.It was a very tough period. I didn't want to change my band but I found myself in a position with studio time.... and I had to ring up and get somebody in. That was the predicament I was in. [15] [16]

Later Life

No longer touring, Klingberg briefly moved to Long Island, New York, with his young family, but the couple divorced shortly thereafter. In 1972, he played on Hypnotized, an album by Puerto Rican singer Martha Velez who was a singer on His Band and the Street Choir. In the mid-70s, he was associated with Madame George Band, an R&B cover combo formed by Morrison's road manager, Rob Robinson [13]. He spent some time living in New York City, but struggled with poor health and difficulty finding work. He returned to Woodstock, where friends helped him stabilize his life, including Morrison's former band manager and his wife, as well as fellow musician Mike Winfield and his wife Barbara. [13]

Klingberg met his long-term girlfriend in Woodstock. From 1979 to 1982, they lived in the hamlet of West Shokan, in the Town of Olive, approximately ten miles south-west of Woodstock. In 1983, Klingberg, his girlfriend, and two of her daughters moved west, intending to reach Austin, Texas. Little is known of his reasons for leaving Woodstock, where he had friends and music connections. Possibly his girlfriend had family in Texas and that motivated the move. [3]

Klingberg never reached Austin, because they were involved in a serious car accident in Oklahoma. Their van was destroyed, and Klingberg suffered a sprained ankle. After recovering, and without a vehicle, he found work as a caretaker at the Cedar Cliffs Estates, in Noble, Oklahoma, and he and his girlfriend settled there. They may have lacked the resources to continue on to Austin, or it was impractical due to his girlfriend's two school-age daughters. According to Woodstock acquaintance Ken Sari, he worked on an oil rig in Oklahoma, but it seems unlikely that he would have sought such a physically demanding, dangerous job, given his chronic poor health. He says "they stayed probably longer than they wanted to because of the money he was making." Klingberg remained in Oklahoma for the rest of his life. [3]

Instruments and Technique

Klingberg was proficient on both electric bass guitar and upright bass. His preferred electric bass was a customized Fender Precision neck mounted on a Fender Jazz body. The neck had been specially modified at guitar shop to fit onto the Jazz body. He opted for the Jazz body because it had two pickups as opposed to the Fender Precision with only one, but as he was tall and with long fingers, he preferred the long neck of the Precision [3]. He played without a pick, utilizing a personalized hand and arm position (as can be seen on this 1970 Van Morrison concert at the Fillmore East) which gave him his distinctive sound. He was also a skilled trumpet player, and played a little guitar and piano as well.

This 1965 Fender Jazz bass with a Precision neck, similar to the one Klingberg played, belongs to musician Gary Shea of Alcatrazz (with Steve Vai and Yngwie Malmsteen), Cooper-Shea, and the Rock Island Orchestra, New England.

Klingberg's former wife recalls his style and technique, and why Morrison hired him:

John did not use a pick or his thumb, he pulled the thick bass strings with his index and middle finger, he would lose the callouses on his finger tips, which meant he would have to play with painful bloody fingers. He never complained, just shrugged. (They were flat wound strings, by the way.) As his finger came off the plucked strings, it would hit the string above, which functioned as a 'stopper'. But there is a slight vibration of the 'deadener' string because of this and it changes the sound of the bass. I remember it quite clearly. The stopper string vibrated very slightly and made a wonderful sound.

I remember when he hadn't played for some months, he came home from a gig with huge blisters on his fingers from the thick wrapped bass strings. He didn't complain and he went right out the next night and played the gig with those blisters.

One time, John was on his way to a gig and he opened his bass case and his bass had no strings. Mike Winfield borrowed them for a gig and didn't tell him. Everyone was in their early 20's, so especially idiotic, but John wasn't that mad, even though he had no spares. There was another bass player in the building and John borrowed his strings and went to the gig.

I never saw him practice, but he never lost his chops. It is unexplainable, but it's true.

John had a slightly dragged out, slightly behind the beat way of playing that Van was looking for. Maybe because Van sings the same way? John called this "fatback" bass...it cannot be learned, it is innate in some musicians, just as it is in some singers, which is why those kinds of singers need a really solid rhythm section to ground them and keep the tune going.

Van disliked musicians who left him "no room"...I remember he once said (and he was a very quiet man, rarely spoke when he was not singing) that he got rid of an excellent piano player because "he played too many notes." (An aside, Van had such a strong Irish accent that it was difficult to understand a word he said, not that he said much...until he started singing and then his words were clear. His voice was amazing, the band would practice at his house in Woodstock on top of Ohayo Mountain Road and he would just stand there and start singing, no microphone, this amazing voice would fill the room.) [13]

In "Jazz Concepts: More Great Intros," bassist, author, and instructor John Goldsby wrote:

Many bassists admire Klingberg's style, and his technique on "Moondance" has become a standard for learning walking bass. Others consider it lagging, lazy, and even sloppy. [20] It should be noted that this was not unintentional; Morrison was exacting in the studio, recording dozens of versions of each song, and "Moondance" in particular. According to flautist Graham "Monk" Blackburn, they made at least six trips to A&R to record the song.John Klingberg is one of those bassists you've heard countless times, yet you probably don't recognize his name. Klingberg lived in Woodstock, New York in the '60s and '70s and made several records with pop legend Van Morrison, including Moondance. Although he passed away in 1985 at age 39, his intro and bass line on this early folk-rock-meets-jazz anthem live on.

Klingberg made an interesting note choice on "Moondance": In bar 3, he plays a leading-tone A# on beat two. The A# is far outside the Am7 chord's tonality, and it pulls the bass line up into the Bm7 on beat three. The effect is subtle, but it's one reason the intro and bass line have a feeling of perpetual motion - that, and Klingberg's warm, flatwound sound. His brilliant A# passing tone on beat two (which he uses consistently throughout the song) made "Moondance" a hit. Okay, maybe Van Morrison also helped push the song into the charts with his vocal. The next time you play "Moondance" for those baby-booming, lizard-dancing party animals at the catering hall, give a wink and a nod to Klingberg for his contribution to the bass canon of classic intros. [3]

Warner Bros. released a total of 11 takes of "Moondance" on subsequent albums of alternates and demos, but the numbering illustrates that at least 22 takes were recorded before Morrison was satisfied. In 2009, engineer Shelly Yakus recalled:It seemed as though every other week we were in the studio recording "Moondance." Van likes to be spontaneous in the studio, but it is a spontaneity that he has to wait a long time to achieve while you are sitting around waiting for instructions. He would try and get himself in the move and get a groove going, but then at the end of it, he'd say 'it's not right, it's not right.' No one knew what was going on. We'd all be pulling our hair out and then we'd have to do it all over again. [15]

Those guys were really good. If you listen to that record, they had a feel that was raw and finished at the same time, and that's very difficult to do. They weren't trying to do that, it's just what they naturally felt in real life, their natural sensibilities...The guys who played together in that band felt what they felt and it comes across like gangbusters, even 40 years later. [8]

Death and Legacy

In 1985, Klingberg suffered a sudden heart attack, dying at the age of 39 at the Norman Regional Hospital in Norman, Oklahoma. He was cremated in Oklahoma. His obituary in the Woodstock Times noted his ashes would be scattered in Woodstock, "the only place he ever felt was home." [17]

Despite his brief career, Klingberg is highly influential among bassists and well-regarded as a musician. Songs such as "Moondance" and "Into the Mystic" are instantly recognizable due to Klingberg's distinct walking bass lines, and "Domino" remains Morrison's highest charting single ever. [18] Moondance is one of the bestselling albums of all time, having received gold, platinum, and multi-platinum awards for more than 3 million copies sold. The album was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999 and named #65 on the list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time" published by Rolling Stone in 2003. Klingberg's playing continues to inspire bassists today, more than 50 years later.

His style of playing was noticed by other bands; Mike McInnerney, sleeve artist for The Who's Tommy, recalls Ronnie Lane of The Faces introducing him to Moondance:

Ronnie had brought Van Morrison's Moondance back from America. I'd not heard it and Ronnie came over to the flat and said 'Look, you've got to come hear this. Just listen to the bass.' So first introduction the album was not Van Morrison's voice - it was the bass. What made the listening experience so special was how Ronnie talked about what this bass player was doing. Traditionally the bass on a record would always be in the background but Ronnie brought it into the foreground by the way he was talking about it. Whenever I hear Moondance now, all I hear is the bass. [19]

Discography

Since Moondance and His Band and the Street Choir were released in 1970, Warner Bros. has released six additional compilations albums of alternates, demos, unreleased versions, and various studio takes. See the Discography page for full list of albums, bootlegs, RIAA sales awards, and charting singles.

References

- "Question Two, Randy and the Soul Survivors". Soul Detective.

- "Request for Info About Jack Schroer". SaxonOnTheWeb.

- "John Klingberg". TalkBass.

- Walsh, Ryan H. (March 5, 2019). Astral Weeks, A Secret History Of 1968. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780735221369.

- Yorke, Ritchie (1975). Van Morrison, into the music. Charisma Books. p. 81. ASIN B0007BMXCA.

- Eskow, Gary (April 1, 2005). "Van Morrison's 'Moondance'".

- Hoskins, Barney (2016). Small Town Talk: Bob Dylan, The Band, Van Morrison, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Friends in the Wild Years of Woodstock. Da Capo Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780306823213.

- Buskin, Richard (May 1, 2009). "Van Morrison 'Moondance'". Sound On Sound.

- "Third World Raspberry". The Boston Sound.

- Brian Doherty (December 27, 2021). "John Plantania - Guitarist with Van Morrison" (Podcast).

- "Classic Tracks: Van Morrison’s “Moondance”". Mix Online.

- personal communication with Robinson's girlfriend

- personal communication with Klingberg's daughter

- "Van Morrison Concert History." Concert Archives

- Turner, Steve (1993). Van Morrison: Too Late to Stop Now. Penguin Group, Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 0-670-85147-7.

- Collis, John (1996). Inarticulate Speech of the Heart. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-306-80811-0.

- "Obituaries". Woodstock Times. 1985-01-31.

- "Domino". Slice The Life. 21 November 2020.

- Neill, Andy (2017-03-07). Had Me a Real Good Time: The Faces During and After. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1468314427.

- "Moondance". TalkBass.